(CNN) — It all started with some boxes that had not been opened for 80 years.

(CNN) — It all started with some boxes that had not been opened for 80 years.

«There was a rumor that there were archives in the Condé Nast offices in New York that nobody had known about,» says Todd Brandow, a photography curator.

«It was difficult to get access, but when I finally got in, they told me that it had all been sold and nothing was left.

«But then the archivist rolled out these boxes of 2,000 prints. It was one of those great ‘oh my God’ moments.»hill to blame for ISIS?

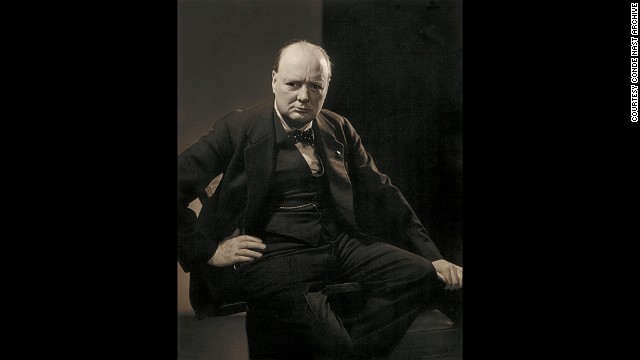

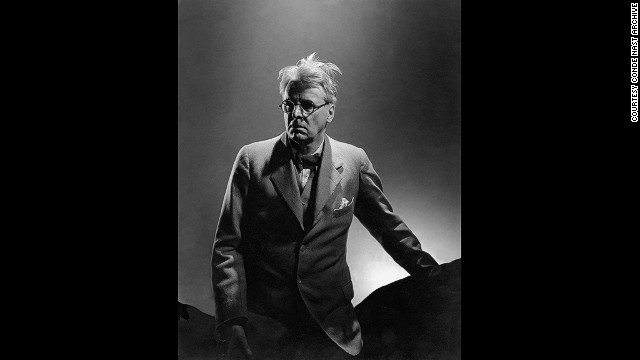

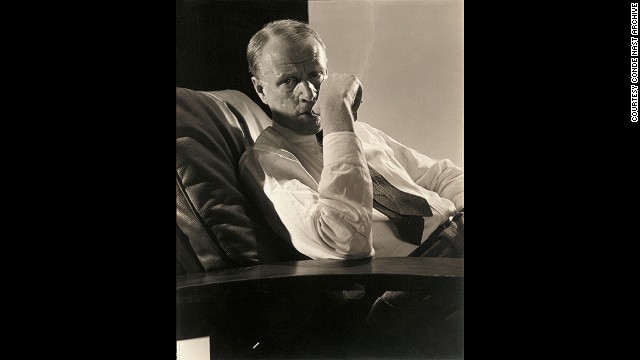

Among the prints were photographic portraits of Winston Churchill, Katharine Hepburn, HG Wells, George Gershwin, Marlene Dietrich, Greta Garbo, WB Yeats, Fred Astaire, and countless other luminaries of the 1920s and 1930s.

None of the pictures had seen the light of day for eight decades, and all had been taken by the pre-eminent photographer Edward Steichen (1879-1973) for Vanity Fair and Vogue.

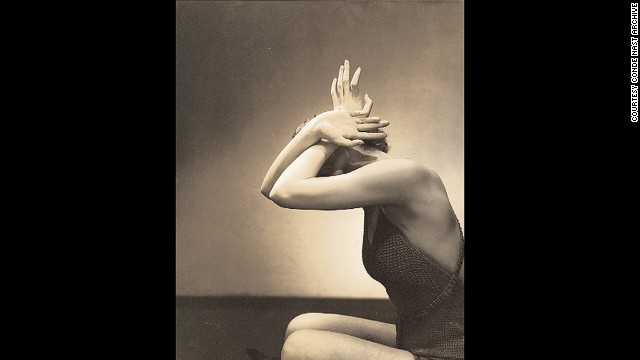

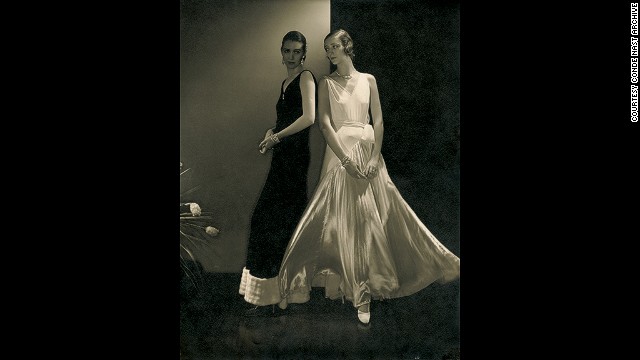

Also included in the stash were Art Deco-style portraits of women modeling designs by Chanel, Lanvin, Lelong, Schiaparelli and many others.

The photographs are now being exhibited at London’s Photographer’s Gallery, where they will show until 18 January.

READ: Apple thinks iPad photography is here to stay

The Picasso of photography

«It was a kid-in-a-candy-store feeling,» Brandow recalls. «They were taken almost 100 years ago but the pictures felt so contemporary, that’s what really excited me. All the poses were so natural, and the vision was so fresh.

«Many of them were fashion pictures, but the women looked like they’d been born wearing those clothes, that they wore them every day. That was Steichen’s skill: he could make people look natural in every sense of the word.»

Todd Brandow, photography curator

During his lifetime, Steichen was recognized as the most important photographer of his age. Even today, says Natalie Herschdorfer, an art historian who co-curated the exhibition with Brandow, he is «one of the top five photographers of all time».

«He was the Picasso of photography,» she says. «He had a 70-year career covering the whole 20th Century. All the genres of modern photography are represented in his work, from the pictorial style of the 1900s to the modernist period. It’s very rare.»

At the height of his fame, Steichen — who borrowed from a range of aesthetic movements such as Impressionism, Art Nouveau and Symbolism to create a distinctive Art Deco style — was being paid the equivalent of $1 million a year by Vanity Fair and Vogue, plus another $1 million by commercial clients.

But after his death he fell from prominence because his widow, Joanna, was extremely protective of the rights to his work, making exhibitions very difficult.

Now, says William A Ewing, the third of the exhibition’s co-curators, the time has come to reintroduce Steichen’s work to the world.

«The skill of any great portrait photographer is to gain an immediacy, an intimacy,» he says. «You feel as if Steichen lives with his subjects. He doesn’t turn them into gods. He brings out their humanity.

«He turned fashion photography into portraiture. He looked first and foremost at a woman wearing a dress, not the dress for its own sake. That’s what connected so powerfully with the viewers.»

William A Ewing, photography curator

From steerage to First Class

The story of how Steichen came to take these iconic photographs — and become a household name — reads like a Hollywood rags-to-riches story.

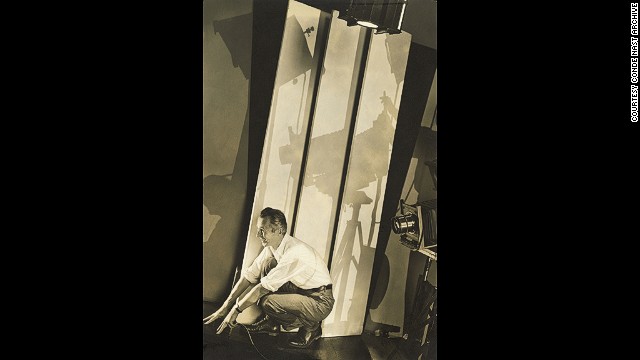

In the early 1920s he had gone through an acrimonious divorce, and had large alimony bills that placed him in financial jeopardy. He was determined to dedicate his life to his art, and had changed his style to a modernist approach, with clean lines, strong diagonals, and high contrast.

But he didn’t know how to make it pay.

In a letter to his sister, he wrote that the outlook was bleak and that he was considering abandoning photography for film, which he thought may have a more secure future.

He traveled from Paris, where he had been during the First World War, to the United States in steerage, alongside impoverished immigrants.

After he arrived, he stumbled upon an article in Vanity Fair in which, to his surprise, he was named as «America’s greatest portrait photographer». He contacted the magazine and was offered a job.

Within a few weeks he was returning to France to photograph Paris Fashion Week. But this time he was on a big salary, and traveling First Class.

«He went from rock bottom to being on top of the world almost overnight,» says Ewing. «You can see this reflected in his pictures, which had a sense of exuberance and confidence.»

Todd Brandow, photography curator

How Steichen worked his magic

It was Condé Montrose Nast himself who had the vision to attract Steichen’s talents to his magazines.

In their discussions, Steichen was quite open about the fact that he had no interest in haute-couture. But Nast persuaded him that «it’s not about fashion, it’s about photography».

«Those were the days before professional models,» says Ewing. «People used to photograph society women. But Condé Nast went to Broadway and hired actors and dancers, who knew how to get into character for the camera.

«This enabled Steichen to work his magic.»

It was this unique approach towards fashion photography, which was firmly rooted in the tradition of portraiture, that was one of the keys to Steichen’s success.

Steichen lived the high life for several years, photographing the world’s most famous faces. But in 1935 he burned out, and resigned to spend his time on horticultural photography, which was his great passion.

«He really was one of the greats,» says Brandow. «He was the founding figure of modernism in photography and the modern woman in fashion photography, as well as modern portraiture.

«Revealing these secret photographs will finally bring him back to the prominence he deserves.»

http://edition.cnn.com/2014/11/18/world/conde-nast-photographs-fred-astaire-greta-garbo/index.html?hpt=hp_mid